truthdig.com/center for study of responsive law

Fedspeak, vague and convoluted answers to economic questions, was popularized by Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Federal Reserve from 1987 to 2006. It allowed him to essentially say “no comment” without admitting that he was avoiding questions.

Fedspeak, which has an uncanny resemblance to what George Orwell called newspeak in “1984,” protected Greenspan from questions he didn’t want to answer in front of either the House Committee on Financial Services or the news media. It exiled public comment from the debate about economics and narrowed the conversation to a small group of economists and business consultants.

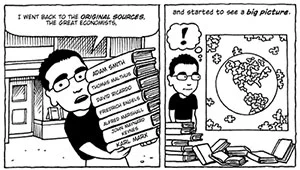

After 30 years of unintelligible fedspeak, writer Michael Goodwin decided that from a self-imposed exile to a small town in India, he would master economics the old-fashioned way: from a thick stack of books. Out of that study came a general history of economics that would be at once clear and simple.

“While the whole picture was complicated,” he writes in the preface to “Economix: How Our Economy Works (and Doesn’t Work),” which came out in September, “no one part of it was all that hard to understand.

“I could see that all this information made a story. But I couldn’t find a book that told the story in an accessible way. So I decided to write one in the most accessible form I knew: comics.”

Image from "Economix: How and Why Our Economy Works (and Doesn't Work), in Words and Pictures"

The visual medium of a graphic account forces the illustrator, Dan E. Burr, as well the reader to think of economics in hard terms. We see France’s finance minister in 1665, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, for example, handing a bag of money to merchants to show what subsidies mean, building a wall to France’s north to symbolize tariffs against the Dutch, and telling a weaver “your fabric must contain exactly 1,408 threads!” while holding a pamphlet entitled “How To Weave” to illustrate quality regulation.

The French regulations were imposed “so their products were good enough to compete with Dutch ones,” Goodwin writes.

Goodwin’s effect is to obliterate the jargon and clichés that dominate The New York Times Business Section and the American Economic Review.

The opening of the book defines capital as the means of production. He lists factories, trading ships and tools, as examples. “Spending money on capital,” he says, “is called investment.”

By building slowly on the basics, he is able to provide the reader with the inner workings of industrial capitalism and global finance. Depicted below each text box is a man with arrows pointing either toward or away from himself to show where capital, labor and money are flowing.

“Capitalists,” Goodwin says, “have been around for millennia, but the capitalist economy is fairly recent. For most of history, most people lived in farming economies governed by tradition.”

“New projects,” he writes above the picture of a man selling a thingumawatchit, “were frowned on” until the Dutch began to “organize their economy around trade and manufacturing” rather than around agriculture, which did not grow exponentially.

Goodwin makes his way through 400 years of economic history. He includes the economic impact of Industrialization, the Bolshevik Uprising and World War II. He sees class warfare as the engine of political struggle. The rich offer bags of cash to politicians, armies and foreign countries for the sake of profit and self-interest.

Once a revolution topples an existing regime, the cycle of power begins all over again.

Goodwin fails at times to credit the role of social and political movements with reform. He gives presidents such as Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama too much credit. Nixon, for example, was deeply hostile to Keynesian economics and the anti-war movement. He instituted modest liberal reforms not because he supported them, but because strong movements pressured him to push through worker-friendly legislation and finally end the war.

“Sometimes Nixon seemed like a lefty,” Goodwin writes, “like when he finally pulled America out of the Vietnam War, reached an understanding or detente with the Soviets, and talked to the Communist Chinese.”

It was an enraged American public fueled by the Pentagon Papers that forced Nixon to take us out of Vietnam.

Goodwin, in the same vein, portrays Clinton and Obama as quasi-progressives who fought the best they could against corporate influence. We should remember that Clinton oversaw the deregulation of the derivatives market, slashed social welfare and artificially lowered the unemployment rate.

Obama reappointed the same people who manufactured the 2008 bailout while expanding the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, keeping private industries satisfied.

Goodwin follows history up to 2012 and the Eurozone crisis. He addresses the demands of Occupy Wall Street.

“But we’ve barely scratched the surface,” Goodwin admits at the end of “Economix.” “I hope you use this book as a foundation for further reading, observation and thinking,” he says. In the back, Goodwin has put together a list of books for further reading. And these are not books written in fedspeak. These are books that take aspects of the economy, as Goodwin has done, and dissect them using normal English.

“I hope you think of this as the beginning,” Goodwin writes on the last page, “and not the end.”